In physics and relativity, Time Dilation is the difference in the elapsed time as measured by two clocks. It is either due to a relative velocity between them (“kinetic” time dilation, from special relativity) or to a difference in gravitational potential between their locations (gravitational time dilation, from general relativity). When unspecified, “time dilation” usually refers to the effect due to velocity.

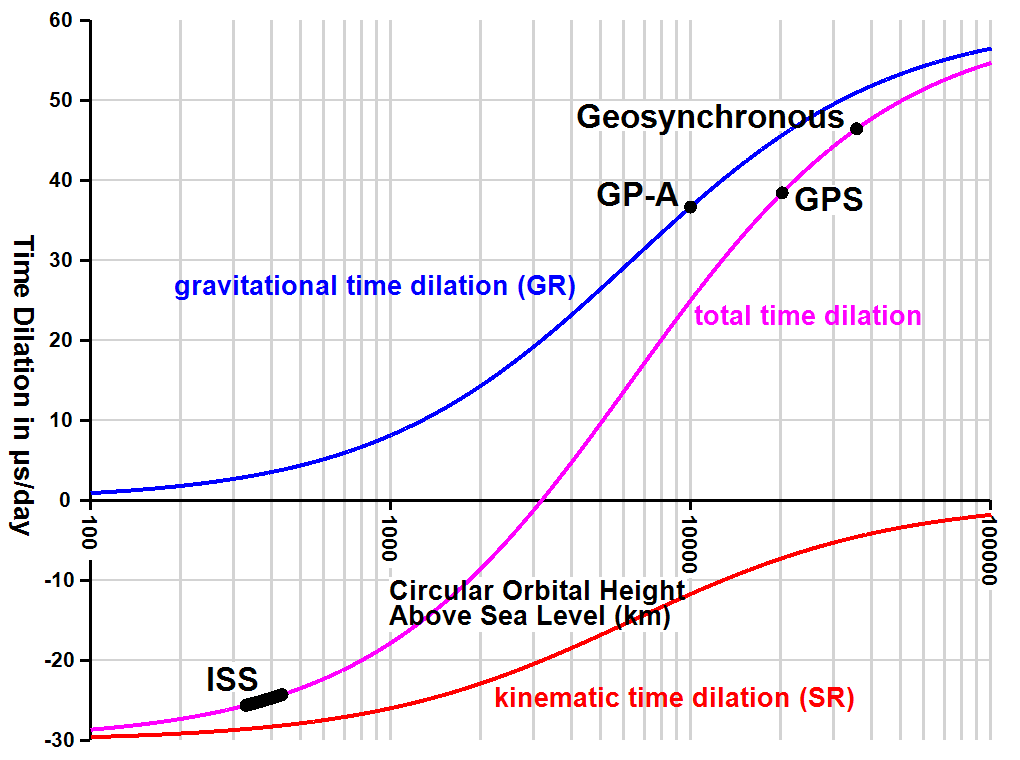

After compensating for varying signal delays due to the changing distance between an observer and a moving clock (i.e. Doppler effect), the observer will measure the moving clock as ticking slower than a clock that is at rest in the observer’s own reference frame. In addition, a clock that is close to a massive body (and which therefore is at lower gravitational potential) will record less elapsed time than a clock situated further from the said massive body (and which is at a higher gravitational potential). These predictions of the theory of relativity have been repeatedly confirmed by experiment, and they are of practical concern, for instance in the operation of satellite navigation systems such as GPS and Galileo.

High-accuracy timekeeping, low-Earth-orbit satellite tracking, and pulsar timing are applications that require the consideration of the combined effects of mass and motion in producing time dilation. Practical examples include the International Atomic Time standard and its relationship with the Barycentric Coordinate Time standard used for interplanetary objects.

Relativistic time dilation effects for the solar system and the Earth can be modeled very precisely by the Schwarzschild solution to the Einstein field equations. In the Schwarzschild metric, the interval $d t_{\mathrm{E}}$ is given by:

$$

d t_{\mathrm{E}}^{2}=\left(1-\frac{2 G M_{\mathrm{i}}}{r_{\mathrm{i}} c^{2}}\right) d t_{\mathrm{c}}^{2}-\left(1-\frac{2 G M_{\mathrm{i}}}{r_{\mathrm{i}} c^{2}}\right)^{-1} \frac{d x^{2}+d y^{2}+d z^{2}}{c^{2}}

$$

where:

$d t_{\mathrm{E}}$ is a small increment of proper time $t_{\mathrm{E}}$ (an interval that could be recorded on an atomic clock),

$d t_{\mathrm{c}}$ is a small increment in the coordinate $t_{\mathrm{c}}$ (coordinate time),

dx, dy, dz are small increments in the three coordinates x, y, z of the clock’s position,

$\frac{-G M_{i}}{r_{i}}$ represents the sum of the Newtonian gravitational potentials due to the masses in the neighborhood, based on their distances ${r_{i}}$ from the clock. This sum includes any tidal potentials.

The coordinate velocity of the clock is given by:

$$

v^{2}=\frac{d x^{2}+d y^{2}+d z^{2}}{d t_{\mathrm{c}}^{2}}

$$

The coordinate time $t_{\mathrm{c}}$ is the time that would be read on a hypothetical “coordinate clock” situated infinitely far from all gravitational masses (U=0), and stationary in the system of coordinates (v=0). The exact relation between the rate of proper time and the rate of coordinate time for a clock with a radial component of velocity is:

$$

\frac{d t_{\mathrm{E}}}{d t_{\mathrm{c}}}=\sqrt{1+\frac{2 U}{c^{2}}-\frac{v^{2}}{c^{2}}+\left(\frac{c^{2}}{2 U}+1\right)^{-1} \frac{v_{\text {॥ }}^{2}}{c^{2}}}=\sqrt{1-\left(\beta^{2}+\beta_{e}^{2}+\frac{\beta_{\text {॥ }}^{2} \beta_{e}^{2}}{1-\beta_{e}^{2}}\right)}

$$

where:

$v_{\text {॥ }}^{2}$ is the radial velocity,

$v_{e}=\sqrt{\frac{2 G M_{i}}{r_{i}}}$ is the escape speed,

$\beta=v / c$, $\beta_{e}=v_{e} / c$, $\beta_{\text {॥ }}=v_{\text {॥ }} / c$ are velocities as a percentage of speed of light c,

$U=\frac{-G M_{i}}{r_{i}}$ is the Newtonian potential; hence -U equals half the square of the escape speed.

The above equation is exact under the assumptions of the Schwarzschild solution. It reduces to velocity time dilation equation in the presence of motion and absence of gravity, i.e. $\beta_{e}=0$. It reduces to gravitational time dilation equation in the absence of motion and presence of gravity, i.e. $\beta=0=\beta_{\text {॥ }}$.

One evening in the spring of 1905, Albert Einstein, then a patent clerk in Bern, after trudging through his day’s work decided to board a tram car on his way home. Einstein would often wrap up his work as soon as possible to contemplate the truths of the universe in his free time. It was one of these thought experiments he devised on that tram car that revolutionized modern physics forever. While receding away from the Zytglogge clock tower, Einstein imagined, what would happen if the tram car were receding at the speed of light. He realized that if he were to travel at 186,000 miles per second the clocks hands would appear to completely freeze. At the same time Einstein knew that back at the clock tower the hands would tick along at their normal pace. For Einstein, time had slowed down. This thought blew his mind. Einstein concluded that the faster you move through space the slower you move through time.

How is this possible? Einstein’s work was heavily influenced by two of the most iconic physicists of all time. First there were the laws of motion discovered by his idol Isaac Newton and second were the laws of electromagnetism, laid down by James Clerk Maxwell. Newton’s laws insisted that velocities are never absolute. But always relative, so that their magnitudes must be appended by the phrase “with respect to”. For instance, a train travels at 40 km/h with respect to someone at rest. However, it only travels 20 km/h with respect to a train traveling 20 km/h in the same direction. Or it travels 60 km/h with respect to another train traveling in the opposite direction at 20 km/h. This is also true for the velocities of Earth, the Sun and the entire Milky Way galaxy. On the other hand Maxwell found that the speed of an electromagnetic wave such as light is fixed at an exorbitant 299,792,458 m/s, regardless of who observes it. However Maxwell’s notion seems incompatible with Newton’s notion of relative velocities. If Newton’s laws are truly universal, why should the speed of life be an exception? This presented Einstein with a daunting dilemma. This conflict between the ideas of Newton and Maxwell can be demonstrated with another of Einstein’s brilliant thought experiments.

Einstein imagined himself on a train platform, witnessing two lightning bolts strike on either side of him. Now because Einstein stands precisely in the middle of the two strikes. He receives the resulting beams of light from both sides at the same time. However, things get more complicated when someone on a passing train views this event while whizzing past Einstein at the speed of light. If the speed of light conforms to the rules of relativity, then the person on the train wouldn’t witness the lightning strike simultaneously. Logically the light closer to the man on the train would reach him first. A measurement of the speed of light made by both men would differ in magnitude, this would contradict an apparently fundamental truth of the universe. Einstein had to make a difficult choice. Either Newton’s laws were incomplete or the speed of light was not a universal constant.

Einstein realized that the two notions could coexist with a small tweak in Newton’s laws. To get rid of the discrepancy in the measurements, Einstein suggested the time itself for the man on the train must slow down to compensate for the decrease in speed, such that the magnitude remains a constant. Einstein called this absurdity “Time Dilation” and his newfound theory “Special Relativity”. Newton believed the time moved unflinchingly in a single direction forward. Einstein, however had just realized the time stretches and contracts varying with velocity. Due to its malleability time like space Deserved its own dimension. In fact Einstein claimed that the two were one and the same. Together they formed a four-dimensional fabric or continuum called space-time upon which the mundane events of the universe would unfold.

Einstein Suggested that massive objects like the Sun didn’t pull bodies like earth with a mysterious Inexplicable tug, but rather curved the fabric of space-time around them, forcing earth to fall down into this steep valley. A highly simplified analogy is the dip in a trampoline made by a falling bowling ball. If a marble were placed on that trampoline the marble would immediately roll towards the bowling ball in the center. This is also true for Earth’s gravity. We are pinned to the ground because space so distorted by the Earth’s mass, pushes us down from above. However the slump in the fabric around Earth is not uniform and Earth’s gravity grows more intense as we move towards its center, where the curvature is at a maximum. Therefore like the marble on the trampoline an object that falls towards the earth accelerates as it races towards the center of the planet. It falls faster when just above the surface than it does say when it is slightly above the atmosphere. But hey, according to special relativity, the faster you move through space the slower you move through time. This means that time runs slower on Earth’s surface than it does above the atmosphere. Now, because different planets have different masses and thus different gravitational strengths, they also accelerate objects at different rates as we have learned this means a variable passage of time. This is what happens in the movie interstellar when the protagonists land on a planet in the proximity of a black hole, the gravity on the planet is so severe that one hour on the surface is equivalent to seven years on earth.

To understand how motion affects time, let’s consider the simplest timekeeping mechanism. A second passes each time the photon is reflected. Let’s imagine two people one in a spaceship slightly above Earth’s atmosphere, and the second on top of a small hill, just above the Earth’s surface. Both are watching a man fall from space towards the ground. Let’s say that the falling man is carrying the photon clock explained a moment ago. What do each of the two men observe as the man falls past them? What they observe is eerily similar to what a stationary person would observe, when watching a ball bounce in a moving train? As the man falls from space, the light in his clock would appear to move in triangles to the two observers. This would mean that the light travels a longer distance consequently stretching the duration of a second. It is obvious that the length of triangles the light traces and therefore the duration of a second is proportional to the velocity of the falling man. When we recall that objects closer to the center of the planet fall faster, we can determine the time would appear to pass slower to the man on the hill than it does to the man in the spaceship above. Of course the difference is infinitesimal. The difference between the time measured by clocks at the tops of mountains and at the surface of Earth is a matter of nanoseconds. Time Dilation affects every clock whether it relies on basic electromagnetism or a complex combination of Electromagnetism and Newton’s laws of motion. In fact even biological processes are slowed down. Yes, that’s right, your head is slightly older than your feet.