Maximum Normal Stress Criterion

The maximum stress criterion, also known as the normal stress, Coulomb, or Rankine criterion, is often used to predict the failure of brittle materials.

The maximum stress criterion states that failure occurs when the maximum (normal) principal stress reaches either the uniaxial tension strength st, or the uniaxial compression strength sc,

$$-s_{c} \lt { s_{1}, s_{2} } \lt s_{t}$$

where $s_{1}$ and $s_{2}$ are the principal stresses for 2D stress.

Graphically, the maximum stress criterion requires that the two principal stresses lie within the green zone depicted below,

Mohr’s Theory

The Mohr Theory of Failure, also known as the Coulomb-Mohr criterion or internal-friction theory, is based on the famous Mohr’s Circle. Mohr’s theory is often used in predicting the failure of brittle materials, and is applied to cases of 2D stress.

Mohr’s theory suggests that failure occurs when Mohr’s Circle at a point in the body exceeds the envelope created by the two Mohr’s circles for uniaxial tensile strength and uniaxial compression strength. This envelope is shown in the figure below,

The left circle is for uniaxial compression at the limiting compression stress sc of the material. Likewise, the right circle is for uniaxial tension at the limiting tension stress st.

The middle Mohr’s Circle on the figure (dash-dot-dash line) represents the maximum allowable stress for an intermediate stress state.

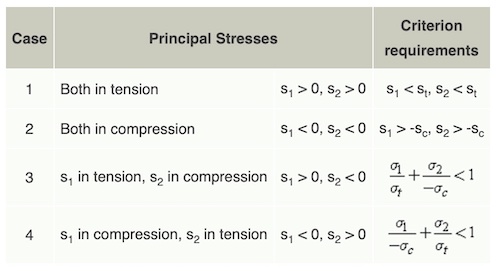

All intermediate stress states fall into one of the four categories in the following table. Each case defines the maximum allowable values for the two principal stresses to avoid failure.

Graphically, Mohr’s theory requires that the two principal stresses lie within the green zone depicted below,

Also shown on the figure is the maximum stress criterion (dashed line). This theory is less conservative than Mohr’s theory since it lies outside Mohr’s boundary.

We know that when we apply loads to an object, like this bracket, if we keep increasing the magnitude of the load, at some point the material will fail. But how can we predict when static failure will occur? What level do the stresses in the object need to reach for it to fail? First we need to define what failure is. For ductile materials failure is usually considered to occur at the onset of plastic deformation. And for brittle materials it occurs at fracture. These points are easy to define for a uniaxial stress state, like a tensile test. They occur when the normal stress in the object reaches the yield strength of the material for ductile materials and the ultimate strength for brittle materials.

But for a more complex case of tri-axial stress, predicting failure is much less straightforward. In fact it’s so difficult to predict that we don’t have one universally applicable method. Instead, we have to predict failure by selecting the most suitable one of a range of different failure theories, each of which we know works relatively well under certain circumstances, based on experimentation. Because they fail in fundamentally different ways, failure theories which apply for ductile materials usually aren’t applicable for brittle materials, and vice-versa. So what does a failure theory do? It’s quite simple - it allows us to predict failure of a material by comparing the stress state in the object we are assessing with material properties that are easy to determine, like the yield or ultimate strengths of the material, that we can obtain by performing a uniaxial test.

The stress state at a point can be described using the three principal stresses, so most failure theories are defined as a function of the principal stresses and the material strength. Probably the simplest failure theory is to say that failure occurs when the maximum or minimum principal stresses reach the yield or ultimate strengths of the material. This is called Maximum Principal Stress theory, or Rankine theory. Although it’s simple to apply, it’s not actually a great failure theory, particularly for ductile materials, for reasons I’ll explain later. Let’s look at some better failure theories for ductile materials. Any good failure theory needs to be consistent with experimental observations we can make about how materials fail.

There is one key observation that failure theories for ductile materials need to capture, which is the fact that hydrostatic stresses do not cause yielding in ductile materials. Let me explain. A general tri-axial stress state like the one shown here can be decomposed into stresses which cause a change in volume, and stresses which cause shape distortion. Stresses that cause a change in volume are called hydrostatic stresses, because that is the type of stress acting on an object submerged in liquid.

For a hydrostatic stress configuration the three principal stresses are always equal, and there are no shear stresses. For a tri-axial stress state we can calculate the hydrostatic component as the average of the three principal stresses. The mechanism that causes yielding of ductile materials is shear deformation. Since there are no shear stresses for a state of hydrostatic stress, this component can be very large and still not contribute to yielding. Yielding is only caused by the stresses which cause shape distortion. These are called deviatoric stresses. The deviatoric component is calculated by subtracting the hydrostatic component from each of the principal stresses. The hydrostatic and deviatoric components can be expressed in matrix form, like this. Here we have described the stress state using the principal stresses, but we could also describe it for an arbitrary orientation of the stress element.

It can be helpful to use Mohr’s circle to understand the hydrostatic and deviatoric components of a tri-axial stress state. For a hydrostatic stress configuration there are no shear stresses, and so Mohr’s circle reduces to a single point, equal to the average of the three principal stresses. Shifting Mohr’s circle horizontally represents an increase in the hydrostatic component. And increasing the radius of Mohr’s circle without changing the average stress represents an increase in the deviatoric component. Since failure of ductile materials only depends on the deviatoric component, a good failure theory for ductile materials should produce the same result regardless of where Mohr’s circle is located on the horizontal axis. This explains why Maximum Principal Stress theory is not a good failure theory for ductile materials - it isn’t consistent with the observation that yielding is independent of hydrostatic stress. Two failure theories which are consistent with this observation are the Tresca and von Mises failure criteria. These are the two most commonly used failure theories for ductile materials.

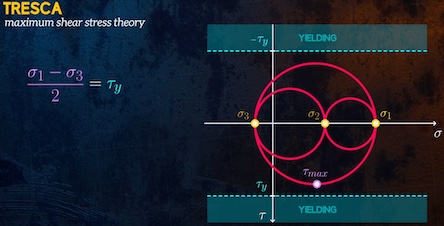

Let’s start with the Tresca failure criterion, which is also called the maximum shear stress theory. It is named after the French engineer Henri Tresca, and it states that yielding occurs when the maximum shear stress is equal to the shear stress at yielding in a tensile test. This can be defined mathematically, like this. And graphically using Mohr’s circle, like this. This theory is consistent with the observation that hydrostatic stresses don’t affect yield. It doesn’t care where Mohr’s circle is located on the horizontal axis. It’s common to express this theory as a function of the principal stresses, instead of as a function of the shear stresses. We can see based on Mohr’s circle for a tri-axial stress state that the maximum shear stress is equal to the radius of the outer circle, which is the difference between the maximum and minimum principal stresses, divided by 2. Mohr’s circle for a uniaxial tensile test at yielding looks like this. The intermediate and minimum principal stresses 𝞼₂ and 𝞼₃ are equal to zero, and the maximum principal stress 𝞼₁ is equal to the yield strength of the material. The shear stress at yielding is equal to half of the yield strength of the material, so we can re-write our equation to obtain the standard formulation for the Tresca theory.

Let’s look at the von Mises failure criterion next, which is also called the maximum distortion energy theory. It was initially developed by the Austrian scientist Richard von Mises, but a number of others were involved in refining it, so it is sometimes called the Maxwell–Huber–Hencky–von Mises theory. It states that yielding occurs when the maximum distortion energy in a material is equal to the distortion energy at yielding in a uniaxial tensile test.

So what is the distortion energy? It is essentially the portion of strain energy in a stressed element corresponding to the effect of the deviatoric stresses. The distortion energy per unit volume can be calculated from the principal stresses using this equation. We know that at yielding during a tensile test the maximum principal stress is equal to the yield strength of the material, and the two other principal stresses are equal to zero. So we can calculate the distortion energy at yielding in a tensile test by plugging in the appropriate principal stress values.

And by equating the distortion energy at yielding with the general equation for a tri-axial stress state, and re-arranging a bit, we get an equation that defines the von Mises failure criterion. Again we can see that this theory considers the difference between principal stresses, and so is independent of the hydrostatic stress. The term on the left is often called the equivalent von Mises stress. If it is larger than the yield strength of the material, yielding is predicted to have occurred.

The equivalent von Mises stress is a common output from stress analysis performed using the finite element method. Contour plots are typically generated to show the distribution of the von Mises equivalent stress within a component, as these allow areas at risk of yielding to be identified. When comparing failure theories it can be useful to plot their yield surfaces. A yield surface is the representation of a failure theory in the principal stress space, which sounds more complicated than it actually is. To keep things simple let’s start by considering a plane stress case, where one of the three principal stresses is equal to zero. By convention principal stresses are ordered from largest to smallest, like this, but since we don’t know yet how the stresses will be ordered, I’ll refer to them as 𝞼A, 𝞼B, and 𝞼C instead. We’ll say that 𝞼C is equal to zero, and so the two axes of our yield surface graph correspond to the two non-zero principal stresses, 𝞼A and 𝞼B.

The yield surface for the Maximum Principal Stress theory is easy to plot - it says that yielding begins when either of these principal stresses is equal to the yield strength of the material, so it looks like this. Yielding is considered to have occurred when the stress state reaches this line. Next let’s plot the yield surface for the Tresca theory. This theory states that yielding occurs when the difference between the maximum and minimum principal stresses is equal to the yield strength of the material. But it’s not as simple as taking the difference between 𝞼A and 𝞼B. Plane stress is still a three-dimensional stress state. In the top right quadrant of the graph both 𝞼A and 𝞼B are positive, and so 𝞼C, which is equal to zero, is the minimum principal stress. The yield surface looks like this. But in the bottom right quadrant 𝞼B is negative, and so 𝞼B is the minimum principal stress. That gives us a yield surface that looks like this.

Repeating this process for the other two quadrants completes the Tresca yield surface. von Mises yield theory for plane stress conditions is defined using this equation when expressed in terms of the principal stresses. We can square both sides of the equation and see that it is of the same form as an ellipse, which gives us the von Mises yield surface. Let’s plot some experimental data for tests performed on ductile materials and see how each of these theories compares. It’s clear that the Maximum Principal Stress theory has large areas where its use is potentially unsafe. So let’s get rid of it, and compare Tresca and von Mises. Both agree well with experimental observations, although von Mises agrees slightly better. The Tresca yield surface lies entirely inside the von Mises surface, meaning that Tresca is more conservative.

If we assume that the principal stresses will increase in proportion to one another as a load is applied, and so the stress paths are straight lines, the difference between the Tresca and von Mises theories is largest for these three configurations. The maximum difference between the two theories can be calculated to be 15.5%. von Mises is usually preferred to Tresca because it agrees better with experimental data, but Tresca is sometimes used because it is easier to apply and it is more conservative. So far we have looked at a plane stress case, with 𝞼C equal to zero. But for a general three-dimensional stress state, 𝞼C will be non-zero. We know that the Tresca and von Mises yield surfaces aren’t affected by hydrostatic stresses, and so to obtain the yield surfaces in three dimensions we just need to extend the plane stress yield surfaces along the hydrostatic axis.

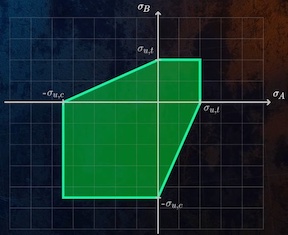

Failure of brittle materials is different to failure of ductile materials. For brittle materials, failure is considered to occur by fracture rather than yielding. And unlike ductile materials, brittle materials tend to have compressive strengths that are much larger than their tensile strengths. This needs to be captured in any failure theory for brittle materials. It also means that to assess failure of brittle materials we need to know two separate ultimate strengths, for tension and for compression.

Coulomb-Mohr theory is a failure theory often used for brittle materials. Unlike the theories we have seen for ductile materials, it considers failure to be sensitive to hydrostatic stresses, and captures the difference between tensile and compressive ultimate strengths. The easiest way to define this theory is using Mohr’s circle. We start by drawing the Mohr’s circles corresponding to failure in the uniaxial tensile and compressive tests. By drawing lines tangent to both circles we create a failure envelope.

Coulomb-Mohr theory states that a material will fail for a stress-state with a Mohr’s circle that reaches this envelope. The Tresca yield criterion we saw earlier is actually a special case of the Coulomb-Mohr failure theory, where we have the same material properties in tension and in compression. The plane stress failure surface for Coulomb-Mohr theory looks like this.

As you can see it doesn’t agree particularly well with experimental data in the bottom right quadrant. Modified Mohr theory is a slight variation on the theory, which better fits experimental data. It is one of the preferred general failure theories for brittle materials. Because failure theories for brittle materials need to account for the effect of hydrostatic stresses, these failure theories converge to a point when extended along the hydrostatic axis. And that’s it for this introduction to failure theories! We’ve covered the most common theories, but there are many more out there which may be more appropriate for specific scenarios.