The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinters, distinguishing them from the organism’s own healthy tissue. Many species have two major subsystems of the immune system. The innate immune system provides a preconfigured response to broad groups of situations and stimuli. The adaptive immune system provides a tailored response to each stimulus by learning to recognize molecules it has previously encountered. Both use molecules and cells to perform their functions.

Nearly all organisms have some kind of immune system. Bacteria have a rudimentary immune system in the form of enzymes that protect against virus infections. Other basic immune mechanisms evolved in ancient plants and animals and remain in their modern descendants. These mechanisms include phagocytosis, antimicrobial peptides called defensins, and the complement system. Jawed vertebrates, including humans, have even more sophisticated defense mechanisms, including the ability to adapt to recognize pathogens more efficiently. Adaptive (or acquired) immunity creates an immunological memory leading to an enhanced response to subsequent encounters with that same pathogen. This process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination.

The immune system protects its host from infection with layered defenses of increasing specificity. Physical barriers prevent pathogens such as bacteria and viruses from entering the organism. If a pathogen breaches these barriers, the innate immune system provides an immediate, but non-specific response. Innate immune systems are found in all animals. If pathogens successfully evade the innate response, vertebrates possess a second layer of protection, the adaptive immune system, which is activated by the innate response. Here, the immune system adapts its response during an infection to improve its recognition of the pathogen. This improved response is then retained after the pathogen has been eliminated, in the form of an immunological memory, and allows the adaptive immune system to mount faster and stronger attacks each time this pathogen is encountered.

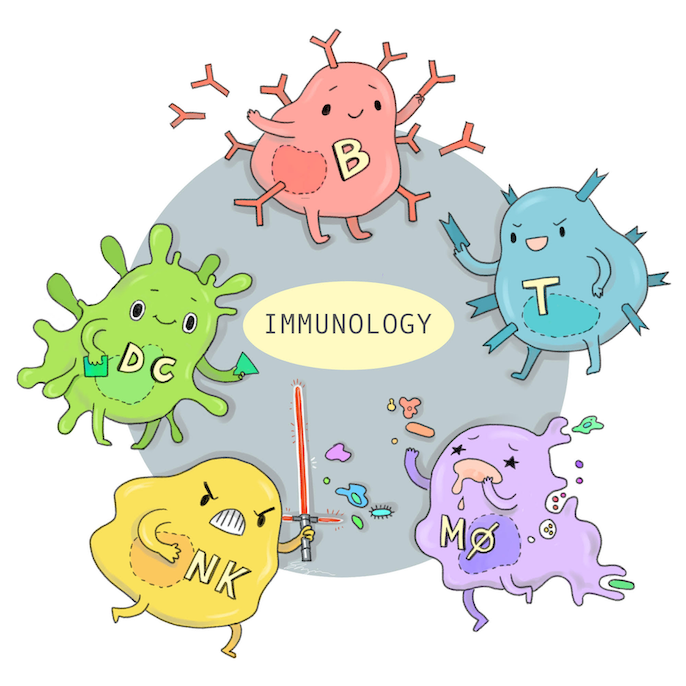

We live in a world filled with bacteria, viruses, and other deadly pathogens. In fact, many of them are trying to invade your body right now. If this thought makes you nervous, feel reassured that your body has its own Department of Defense - your immune system. This network works hard round the clock to protect you from harmful invaders. When a pathogen launches an attack, your immune system organizes a beautifully coordinated counter-attack to destroy the pathogen and keep you healthy. Unfortunately, your immune system can make mistakes, including: not destroying diseased or harmful cells (infections and cancer), reacting to non-harmful substances (allergies), or going rogue and attacking your own cells (autoimmune diseases). The immune system is fascinating and complex, and we want to share with you what’s going on in the field of immunology.

When a virus enters your body, it will attach itself to one of your cells and inject its DNA or RNA into it. This is like a blueprint for your cells: containing instructions on what the cell has to make. So, in this case, the virus’s RNA will tell your cell to make more copies of the same virus. They become virus factories, pumping out new copies of the virus that can infect even more cells. Naturally, our bodies have a defense system for foreign intruders. The immune system attacks any protein, virus, or bacteria that do not belong in our bodies. But it takes a few days for it to learn how to attack the intruder. Meanwhile, the virus factories are running non-stop, quickly replicating the virus and spreading it in your body. In other words: you start experiencing symptoms of whatever has infected you.

After a few days, however, your immune system has figured out how to attack the virus and will start to produce antibodies. These attach themselves to the virus, preventing them from infecting more cells and marking them for destruction. As you can see, the immune system is remarkable, but it’s also slow to mount an attack. That’s the reason why we get sick in the first place. So to give it a helping hand, we developed vaccines. The main idea is to train your immune system to recognize and fight off an infection before it has occurred. Almost like showing your immune system a mug shot of the virus and saying: “if you see this, kill it.” There are various types of vaccines, but let’s take a look at mRNA vaccines, the new kid on the block.

To understand how they work, let’s take the COVID19 pandemic as an example. You might have seen pictures of the virus, with its distinctive spikes. These spikes allow the virus to attach to specific cells in your body (ACE2) and infect them. Now here’s the key idea for the COVID19 vaccine: what if we could train our immune system to recognize these spikes by having our body produce them? To do that, researchers took the virus’s blueprint, its RNA, and isolated the part responsible for producing the spikes. Armed with this blueprint, they created mRNA or messenger RNA. This is a special form of RNA that can enter your cells and give them instructions. In this case, the RNA contains instructions to build the spikes of the coronavirus, not the virus itself, just the spikes. So mRNA vaccines contain instructions for your cells that tell them to build a part of a virus in large volumes, almost like giving them a recipe to follow.

Once this is happening, your immune system kicks into action and start learning how to attack these intruders. Again, it takes time for the immune system to fight off these spikes, but you won’t get sick because it’s only the spikes, not the virus itself. And that’s it! Your immune system has learned how to attack the spikes of the coronavirus. It destroys all the spikes and even breaks down the mRNA vaccine itself. The only thing left in your body are special “B cells” or memory cells. These can linger around for months or years until the same virus infects you again. When that happens, the B cell can produce the correct antibodies right away, preventing the virus from spreading and making you sick.

What’s interesting about this mRNA technique is that it’s relatively quick to develop a vaccine as soon as we know the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. And secondly, because the vaccine only makes our body produce a part of a virus, we can’t get sick. More traditional vaccines use weakened versions of the actual virus. This also triggers an immune response but could also give you mild symptoms. Now you know how mRNA vaccines work, what about their safety? The biggest misunderstanding about this technology is that the mRNA in the vaccine can enter our cells and changes our very own DNA. But that’s not true. mRNA is very fragile and only survives a few hours in our bodies.